Behind the scenes for the Blog and Travelling in 2025

I thought I’d finally get around to writing up a technical blog post about the blog itself and the technical side of all those travel blog posts (about 6 months after I intended to start this!). The post is broken into 3 main sections:

- Details about the GitHub blog itself

- The interactive travel map using Leaflet

- The whole process of curating and posting 6 months of travel media

This GitHub blog

This blog was created using the Al-folio template https://github.com/alshedivat/al-folio and then customised. You can preview this base template at https://alshedivat.github.io/al-folio/ and you’ll probably recognise a lot of the structure!

I made quite a few tweaks and changes (the details of which I’ll leave in the my github history for those who are reeeeaaaally eager to see them), but probably the nicest change I made to jazz up the website was to put the jekyll-animate-elements package into the repository Gemfile, so that all the web elements have short animated transitions on load.

The interactive travel map using Leaflet

Back at the start of the year I had grand plans about learning some Leaflet/JavaScript while we travelled so that I could make some cool visualisations of where we were. Best laid plans quickly evaporate away when you start enjoying a holiday, so beyond the blog posts themselves I never found(made) time to do so (and have little regret!)

I did however mention my plan to learn Leaflet/JavaScript to one of my colleagues at the CeR, Nick Young, before I set off travelling and lo and behold within a few days he had wrustled up a quick example or two!

From these two examples, one for road routing and one for straight lines between points, I had the bones to get me started in making our very own travel map for our 6 months!

You can find all the code for this Leaflet map in this repository here. The html page works by loading in the geojson file containing all the trip route + metadata, which itself is generated by a Python script that uses a csv file containing the blog metadata. Routes are generated by querying the Open Source Routing Machine (OSRM) to provide A to B routes.

The first hurdle I had was to combine both the driving route and straight line behaviour of Nick’s examples, so that we could handle driving, flights, and boats along the routes. An extra column or two of flags in the csv file to distinguish travel method sorted this out.

The next challenge I faced was the desire to have clickable markers with thumbnails to take you to the various blog posts. I made this even more complex when I decided to have a separate smaller marker for day-by-day links. Fortunately all of this could just about be done with tooltips in Leaflet v1, and I was able to add in a menu toggle too for these markers. Leaflet v2 looks like it will be much more configurable (and prettier) for markers, but at the time of creating the map almost none of the 3rd party leaflet modules were compatible with the freshly released Leaflet v2.

Finally, the biggest headache I had was attempting to do train routing in Japan. The OSRM API isn’t configured to do train routing (presumably due to abuse potential) and so I needed to run a local instance of their routing server (via WSL). Modes of transport can be configured via profiles, and fortunately I stumbled across this cracking little repository that already has profiles for regular and freight trains. Using this profile, the Japan railmap, and the local routing server worked to some degree, but I ended up with quite a few weird routes, and some seemed impossible to achieve! It took days before I finally realised that my trains were stuck to the heavy-duty shinkansen lines, and that by default the routing server was configured for heavy-duty freight trains rather than the lighter-weight regular trains. Visually debug maps is the key!

Curating and posting travel media

Why is this even a section?

You may be asking “Hey Mike, why is this even a section? It doesn’t sound very techy to me”. Well, that’s probably true if you’re using a typical social media platform where you can simply snap and publish content, but here was our situation:

- Some dummy chose to do this in Github to make this more challenging.

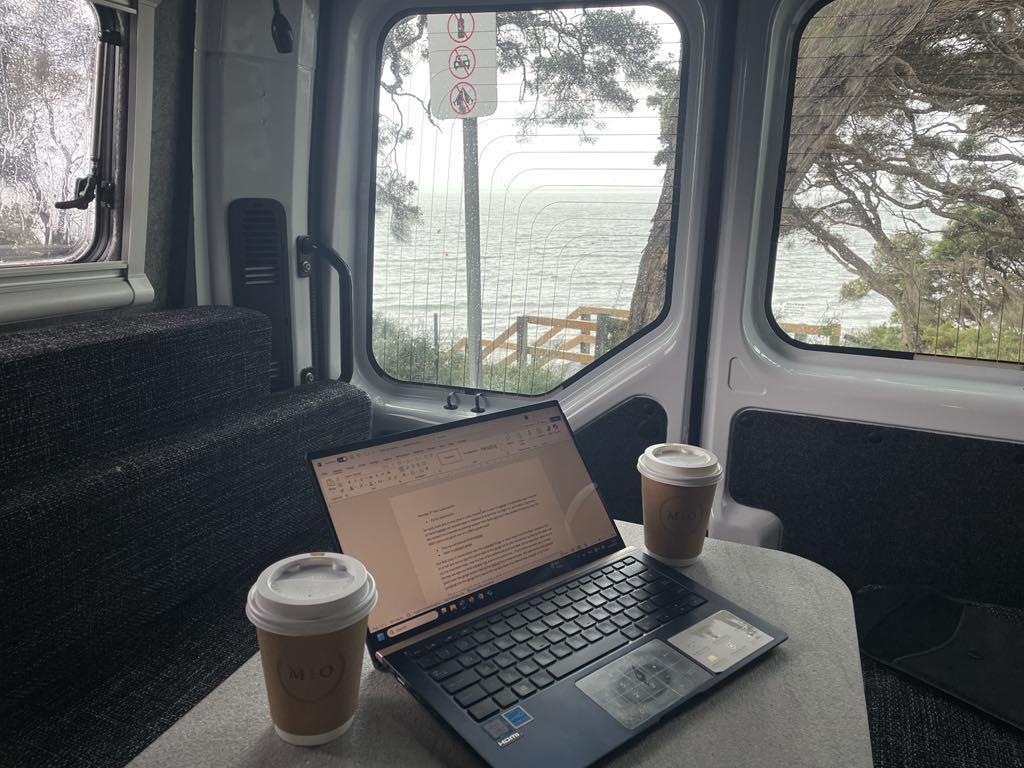

- Our travel computer was my wife’s light-weight 8-year old notebook with 8GB of RAM (5.5GB of which is consumed by Windows 11).

- Between us we took over 10,000 photos and videos across our devices.

- Our media capture devices consisted of an Android phone, iPhone, DSLR, and GoPro.

- GitHub repositories, websites, and browsers are all adverse to hosting GBs of media.

Fortunately, workflows are my jam! So during some very rainy days early in our travels I rustled up some prototype workflows for collating our media and posting blogposts, and polished things up later so that we could keep on top of posts while travelling (Japan ended up being too fun to keep that posting momentum going)!

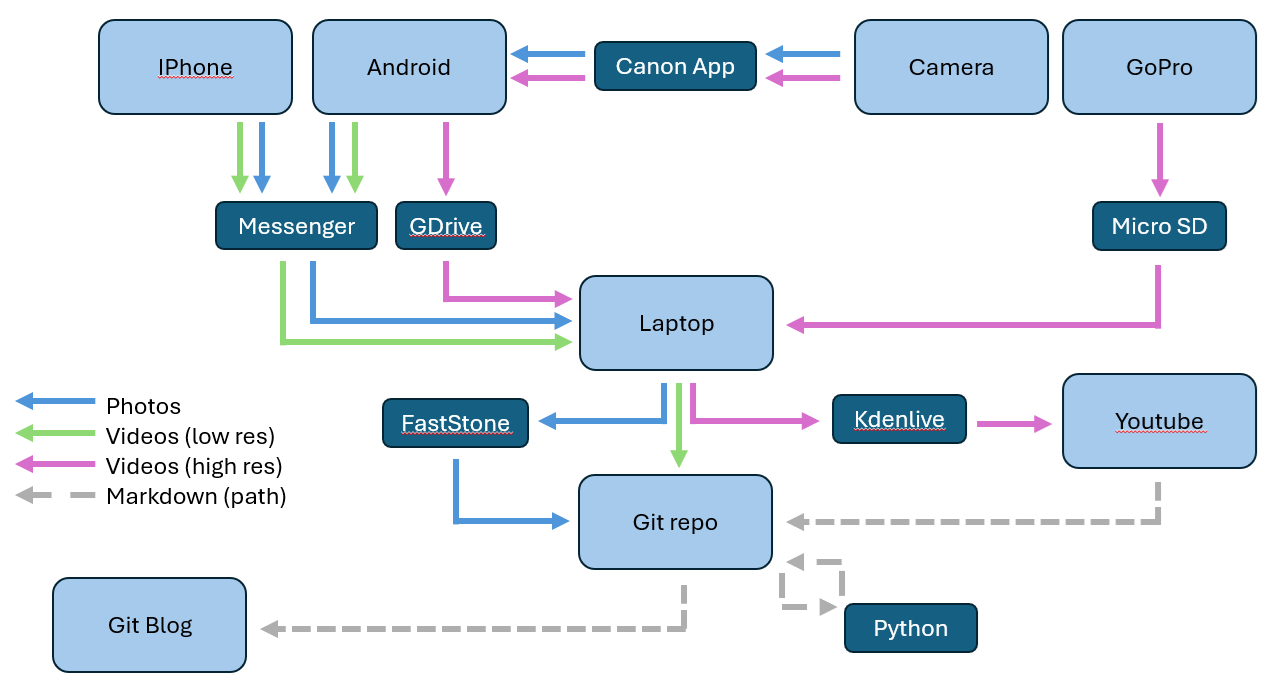

Here’s the final workflow for sorting everything out, and below is far more detail than anyone asked for!

Collating and sorting images

Sifting through the 10K+ photos

Nobody wants to see all 10K+ photos that we took on our travels, nor do I fancy hosting that many, so our first step for any blog post was to manually sift through all the relevant photos on our devices to pick out which photos we wanted to publish. Once selected, we need to consolidate all of these into the GitHub repo.

Transfering media to the laptop: Phones

Attempt 1: Initially I tried to upload photos from both the Android and iPhone into our Google Drive so that they could be downloaded to the laptop. While this does work, it sends across the full size raw photos which clock in at around 8MB per photo nowadays. This soon became a drain on our phone data plans as they often did double effort in hotspotting the laptop, and our (free plan) Google Drive quickly increased in size.

Attempt 2: Google Drive didn’t seem like a sustainable option for data transfer, so instead I turned to Facebook Messenger to send photos from phones to the laptop. This was relatively simple, avoided filling the Google Drive, and had the added bonus that Facebook did a hefty amount of compression which was suitable for eventual website hosting. Oh, and it also saved our data plans from being hammered.

Transfering media to the laptop: Camera

A lot of our “hero shots” were taken on my DSLR (it’s as if it was designed to take good photos!), but unfortunately my DLSR uses a regular sized SD-card and our laptop only had a micro-SD slot. To transfer these shots to the laptop I needed to use the Canon Camera app on my phone to bluetooth/wifi transfer photos from my camera to phone, and then follow the usual phone->laptop method. The downside was that my raw photos were mostly stuck on the camera SD card, which only gave a 64GB pool for the high-resolution media for the entire 6 months (which finally filled up capturing the whale videos in Canada!).

Curating the blob of photos

Using Messenger to consolidate media and perform internet-ready compression worked great, albeit with an annoying caveat: the filenames became anonymised random strings. In addition the time taken metadata field wasn’t present on all images (be it an Apple vs Android issue, or Meta stripped them out) which made it tricky getting photos into the correct order.

To do so I ended up using a great little piece of software called “FastStone Image Viewer”. This comes with all the basic photo library functionality a photographer needs, including the ability to do drag-drop ordering, and bulk processing of files. Using this I was able to sort photos into the right time-order and then bulk rename them in numerical ascending order (i.e. 1.jpg, 2.jpg, 3.jpg etc). I was also able to convert Canon’s .cr3 raw format into jpg, something I hadn’t already done with my Python scripts below.

Sorting images was still one of the main bottlenecks of this whole process, especially if I had several days of photos to unscramble, but FastStone made it considerablly easier to do.

Collating, editing, and hosting videos

Transfering and hosting videos

Videos proved a connundrum for the blog. We only took videos of the most incredible stages of our travel, but we simply couldn’t throw GBs of videos into the Github repo, and compressing them to low-resolution managable sizes all but defeated the purpose of taking the videos. So instead I ended up with two methods:

- for short videos that were still okay at low resolution I simply used Messenger to transfer and compress them, and then hosted them in the GitHub repo.

- for high resolution videos I used Youtube to host the video and then embedded it in the blog.

GoPro videos were easy to transfer: I simply plugged the micro-SD card into the laptop and moved files across. For high-res phone videos I bit the bullet and transferred them into Gdrive and then to the laptop, ideally when we had campsite wifi to use. for the Camera videos I had to transfer them to my phone via the Canon App bluetooth/wifi, and then to GDrive and the laptop.

Editing footage together using ClipChamp and KDEView

Our GoPro was used for snorkelling and was strapped to our wrist…. we definitely needed to edit the videos! For earlier snorkel trips I (regrettably) used Windows ClipChamp to trim and sort video footage. It wasn’t until far later in our trip that I truely realised the downsides of using ClipChamp:

- ClipChamp is browser-based and so requires an active internet connection even for local files.

- ClipChamp can read in 50-60FPS footage, but can only write out at 30FPS…

And so for our later videos I turned to Kdenlive as a freeware video editing alternative, which had neither of the above shortcomings. I believe I still have the raw GoPro footage still on it’s SD card, and so the possibility still exists that I can reproduce the earlier videos but at 50-60FPS after all.

Python script for thumbnails and blog post integration

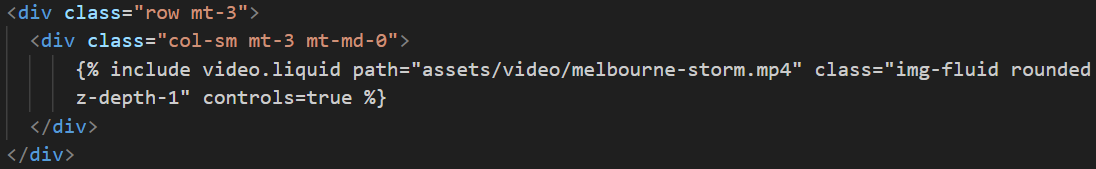

Once all the media is collated into the repo, or youtube, I needed to actually work it into the blogpost markdown files. I did this by first drafting out the text of the blog post, and then inserting markers for the numerically sorted images and named videos. Al Folio offered a couple of ways to embed media in the blogposts, but here are the typical code snippets I needed to insert into a post:

- embedding multiple photos using thumbnail previews

- embedding videos from the repo or youtube

Ironically I had to use the image embedding itself to display that code, as markdown didn’t enjoy commenting out the JavaScript include tags!

I wrote a quick Python script to perform image format conversions to .jpg (typically photos were .webp or .JPG after Messenger compression), generate image thumbnails with via very basic photo-scaling, and then write those filepaths into the drafted markdown blogpost. The script searched through the markdown for any new lines beginning with either * IMG or * VID and then inserted the above code blocks using any filenames found afterwards i.e. the above code blocks are generated from the following markdown lines:

* IMG 2,3,4

* VID melbourne-storm

Once the Python is run, this would generate a new copy of the blog post with image and video code inserted that I could proof-check before committing to the Github repo.

That’s a wrap!

Hopefully this gave you a bit of an insight into what it took to get the blog going while we travelled, and it’s certainly cemented that I couldn’t be a vlogger for a job!

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: